Quintessential Tarot

Numerology and Symbolism of the Tarot de Marseille

Exploring the role of the Quintessence (Fifth Element) in the structure and meaning of the Major Arcana.

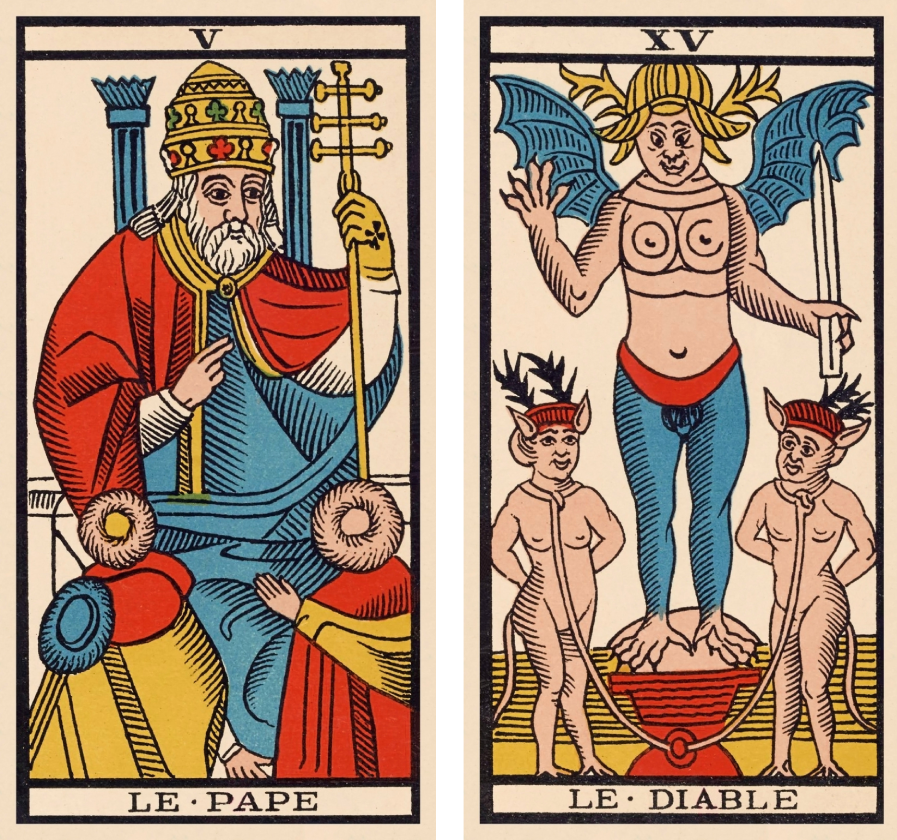

The fifth and the fifteenth arcana share astonishing similarities in composition. Both are spiritual figures, with their right hands raised before their two diminutive followers. Le Pape holds his staff, a good shepherd leading his flock. Le Diable holds a torch, leading his impish followers into darkness. They both wear ornate crowns: le Pape, a triregnum symbolising the Holy Trinity, while le Diable dons a horned helmet, symbolising his violent and animalistic inclinations. The three figures on Le Pape could also represent the Trinity, while the three on Le Diable would represent the anti-Trinity (Satan, the Anti-Christ, and the Spirit of the Age).

“The god of this age has blinded the minds of unbelievers, so that they cannot see the light of the gospel that displays the glory of Christ, who is the image of God.” - 2 Corinthians 4:4

Le Pape’s hand offers a blessing; the two extended fingers stand for the visible world (what is apparent), while the two bent fingers represent the invisible (what is concealed and transcendent). This gesture signifies “as above, so below”. Le Diable mirrors this with his pose, one arm pointing above and the other below. Bat wings, a sign of individual power, led Lucifer to the depths, while le Pape has a pair of narrow pillars, symbolising the firm structure of the church and the narrow path of Christ. Le Diable stands on a pedestal, indicating the high view he holds of himself, while le Pape is seated, slightly hunched, perhaps suggesting the humility of Christ. Both cards focus on a bodily sense: the Pope emphasises hands, while the Devil, on many tarot de Marseille, emphasises eyes. Hands bless and do good work while staring eyes can either threaten or seduce. Eyes represent both attraction and frightful aggression. In the V and XV positions, both cards embody the transformative nature of the fifth element, the Quintessence, in both positive and negative facets.

Often in myths and folktales, the hero who encounters the devil must deceive him through cunning. It is worthwhile meditating on the story of Jacob and Esau, where Jacob, the hero of Israel, deceives Isaac to receive the father’s blessing. The delightful story of Brother Lustig from Grimm’s Fairy Tales plays with this concept, where the hero tricks the devil to escape hell and deceives St. Peter to sneak into heaven.

“I can tell you stories that say if you meet evil, you must fight it, but there are just as many that say you must run away and not try to fight it. Some say to suffer without hitting back; others say don’t be a fool, hit back! There are stories that say if you are confronted with evil, the only thing to do is to lie your way out of it; others say no, be honest, even toward the Devil, and don’t become involved with lying. For all these, I could give you examples, but it is always a yes and a no. There are just as many stories that say the one as the other. It is a complete complexio oppositorum, which simply means that, post eventum, I disappointingly came to the conclusion that really it should be like that because it is collective material! How, otherwise, could there be individual action? For if collective material is completely contradictory, if our basic ethical disposition is completely contradictory, only then is it possible for us to have an individual, responsible, free conscious superstructure over those basic opposites. Then we can say that in human nature it would be right to do this or that, but I am going to do this, the terrium, the third thing, which is my individuality. There would be no individuality if the basic material were not contradictory. That was my comfort after having discovered the terrible truth of the contradictory structure!” - Marie-Louise von Franz, Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales, p. 89

Excerpt from: